Someday, Maybe is a novel about grief. Eve loses her husband to suicide and struggles to overcome the depression and trauma of not only the loss of her beloved, but also the shock of his decision and the guilt she feels for not seeing the signs. He leaves no note, gives no warning, and creates a mess of family affairs and other loose ends. In addition, his mother pours out all her anger onto Eve, sinking to horrific, but believable, depths of verbal and legal cruelty at a time when Eve is least equipped to defend herself.

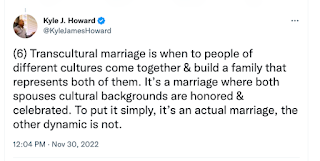

As she grieves, we see flashbacks to Quentin and Eve's love and life together. As the novel progresses, those flashbacks become increasingly more honest. Eve begins to lose the gloss that distorted her view of Quentin, and begins to accept that he was not perfect, just as she isn't, but that both are still worth loving. One thing I like about the novel is that it centers an interracial marriage, with all of the nuances that brings, but the main conflict is not "them against the world." I appreciated the way it balanced the effort to normalize their union while still acknowledging the distinct issues it faces. At its core, the main conflict is grief, and the fact that the lovers are of different races is handled with honesty while still allowing Eve and Quentin to deal with the sorts of problems that most couples face. Even the animosity from Aspen, Quentin's mother, tinged as it might be with racism, is ultimately about control. I got the impression that while Aspen sees Eve as particularly unacceptable fas a daughter-in-law as a Black and Nigerian woman, nobody would have been acceptable. Her relationship with Quentin is one of those toxic relationships in which the mother tries to use her son as a surrogate partner after the death of his father, a dynamic also born out of unresolved grief.

However, despite some of the critiques of the novel I've read, which I'll discuss later, the novel is not so heavy as to become torturous reading. Not only does the novel oscillate between the utter despair, shock, and grief that Eve is enduring and the mostly happy flashbacks of her life with her husband, but the tone of the novel itself has a dark, sardonic, self-deprecating humor that makes the sadness of it more palatable. One thing that Nwabineli does very well is keep the tone dialed mostly to dark humor, but then periodically remind us of the horror of what actually happened. When Eve is sorting out her feelings for her mother-in-law, balancing a merciful pity for the woman's grief against a justified indignation against her cruelty, she remarks, "She wasn't the one who slid in his blood." Every so often, Nwabineli throws a punch that lands flush, disrupting the dark humor with the pain of reality. And immediately after the punch lands, she can retreat into a rose-tinted flashback or another self-deprecating quip that resets the mood of the novel.

In addition to the tone, there is a sense of hope produced by Nwabineli's choice of perspective and her strong sense of voice. By writing this novel in first person, Nwabineli is effectively reminding the reader of one of the oldest truths of fiction. If the main character tells the story, then she must survive in the end. In any first person narrative, no matter how many gunshots or breathless close calls, no matter how bleak or dangerous things get, the reader knows that the main character will live to tell the story. In Someday, Maybe, the person telling the story is the Eve who has survived, in whatever form that takes. The narrator is the Eve who no longer spends each day in bed, roused only by loving family members. The Eve telling the story no longer flinches at every hurdle or setback life throws at her. She has overcome, or at least is in the continuing process of overcoming, and this is probably the reason the novel takes the darkly humorous tone that it has. The Eve telling the story can afford to shake her head at the former Eve who easily falls apart at the slightest test of her resolve. In the future, she has the energy and strength to spare. She has survived the worst, and tells the story from the mountain top, or at least high on its face, even if the story itself takes place in the valley.

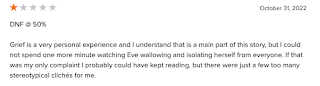

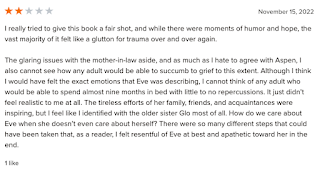

This brings me to some of the critiques I've read about Eve's grief process. In choosing the novel, I read some reviews, and found several that put me off the book a little, even though I still wanted to read it. Several of the reviews I found took issue with Eve "wallowing" in her grief. They found her either unlikable or unbelievable because she pushes away the people who try to help her and engages in behaviors that are either unhelpful or downright self-destructive to her healing process. I hate to give these reviews oxygen by linking to them, but I do want to respond to their criticism, so I'm posting screenshots here.